Scientists who study climate change confirm that these observations are consistent with significant changes in Earth’s climatic trends. Long-term, independent records from weather stations, satellites, ocean buoys, tide gauges, and many other data sources all confirm that our nation, like the rest of the world, is warming. Precipitation patterns are changing, sea level is rising, the oceans are becoming more acidic, and the frequency and intensity of some extreme weather events are increasing. Many lines of independent evidence demonstrate that the rapid warming of the past half-century is due primarily to human activities.

The observed warming and other climatic changes are triggering wide-ranging impacts in every region of our country and throughout our economy. Some of these changes can be beneficial over the short run, such as a longer growing season in some regions and a longer shipping season on the Great Lakes. But many more are detrimental, largely because our society and its infrastructure were designed for the climate that we have had, not the rapidly changing climate we now have and can expect in the future. In addition, climate change does not occur in isolation. Rather, it is superimposed on other stresses, which combine to create new challenges.

What is new over the last decade is that we know with increasing certainty that climate change is happening now. While scientists continue to refine projections of the future, observations unequivocally show that climate is changing and that the warming of the past 50 years is primarily due to human-induced emissions of heat-trapping gases. These emissions come mainly from burning coal, oil, and gas, with additional contributions from forest clearing and some agricultural practices.

Temperatures are projected to rise another 2°F to 4°F in most areas of the United States over the next few decades. Reductions in some short-lived human-induced emissions that contribute to warming, such as black carbon (soot) and methane, could reduce some of the projected warming over the next couple of decades, because, unlike carbon dioxide, these gases and particles have relatively short atmospheric lifetimes.The amount of warming projected beyond the next few decades is directly linked to the cumulative global emissions of heat-trapping gases and particles. By the end of this century, a roughly 3°F to 5°F rise is projected under a lower emissions scenario, which would require substantial reductions in emissions (referred to as the “B1 scenario”), and a 5°F to 10°F rise for a higher emissions scenario assuming continued increases in emissions, predominantly from fossil fuel combustion.

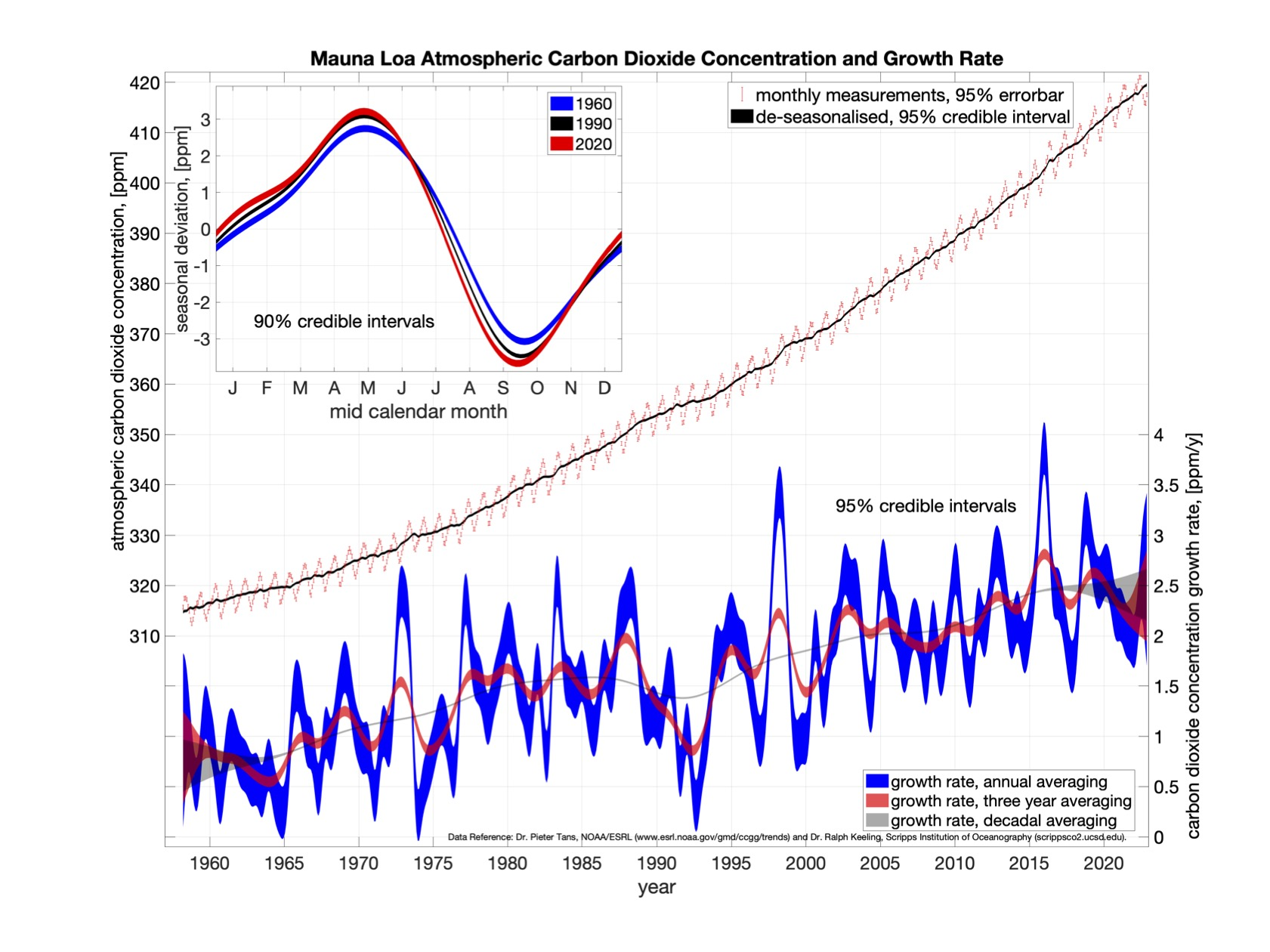

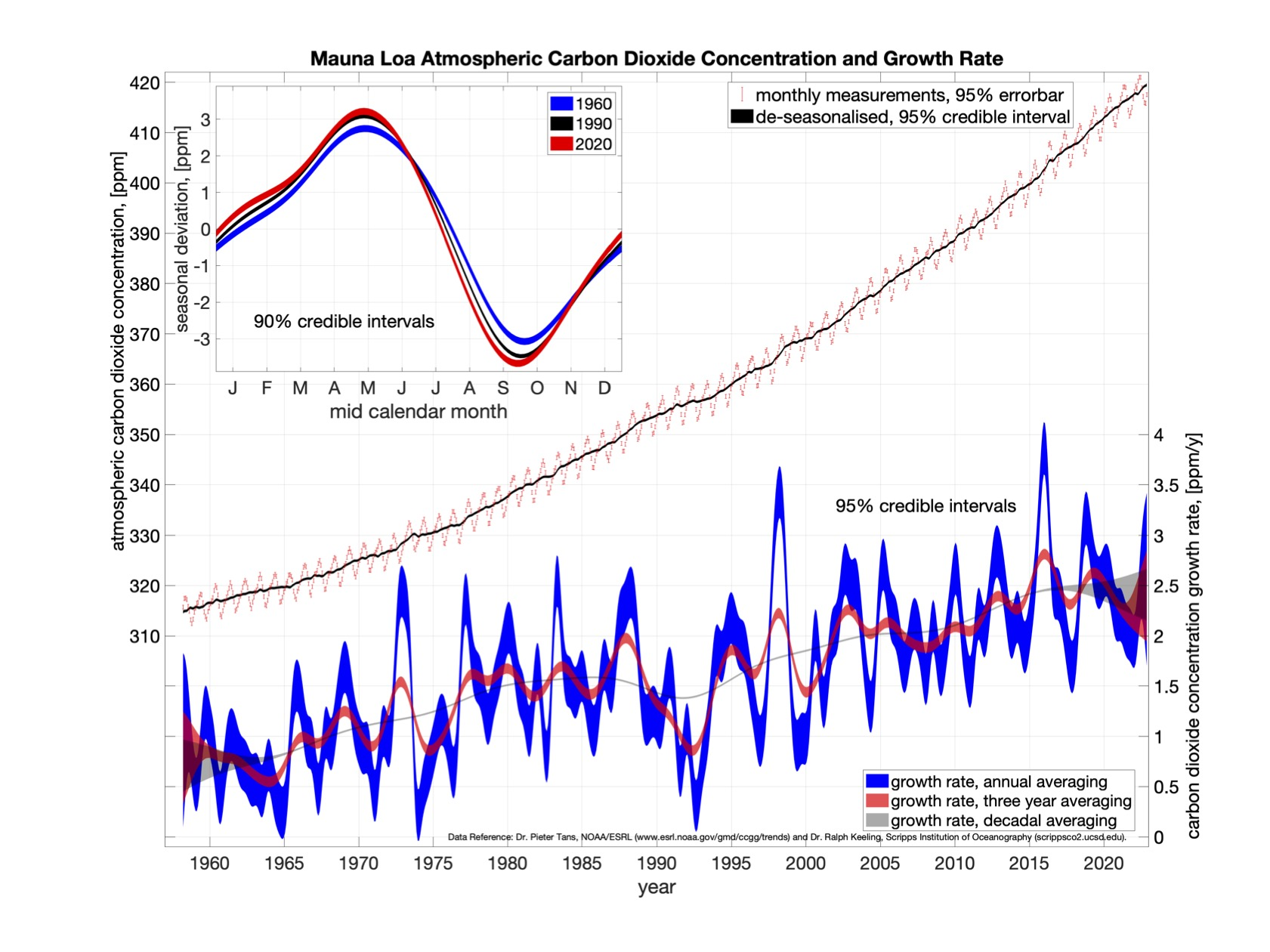

In 1960-1970 the growth rate was slightly less than about 1 ppm/y, but the growth-rate has been steadily increasing, reaching 2.41±0.26 ppm/y (mean ± 2 std dev) at the middle of 2022. This means that currently, the concentration of carbon dioxide is growing by about 2.41 ppm per year.